In those days, absolutely everything about the marriage was wrong: She was Catholic; he was Protestant. She was a young widow; he had never been married. She had a child whom he adopted, but he loved children and wanted his own. That never happened. Both of their families lived in the north of the state. Because of his work, they moved to its very southern edge where there were no cousins, no aunts, no family. She sent the child to a Catholic school; his Protestant mother did not approve. She wanted the husband to become Catholic; he didn’t. The tensions were everywhere.

So, one day I said, “Mother, tell me about my real father.” She looked at me long and hard.

“You have a father,” she said to me. “I know,” I said.“But I want to know what my own father was like.” She thought a moment. “Joan, your father was very young when he died. I have no idea what he would have been like had he lived, and I don’t want you idolizing a myth.” I was ten years old.“But, Momma,” I argued, “we would all have been Catholic and that would have been better.” I was the only child in my class with a Protestant father, and I was clearly tired of explaining to people how such a strange thing could ever have happened.“Joan,” she said firmly, “life goes on. We don’t know why your father died. That is for a reason that we can’t understand yet. But we do know that God is in it with us. That’s all we need to know. There is nothing else to say.” And she didn’t.

But if it had not been for that strangely skewed beginning, I know when I look back, my own life would never have developed the way it has. The insight that life is about “now” could never have come so young. The awareness of otherness would not have come for years—maybe never. The understanding of what it means to be different and marginal—light years ahead on some things, completely out of it on others—might never have seared and stretched my soul.

My life wasn’t neat; it didn’t evolve the way the social scripts said it should. There was no clear beginning, middle, or end. It was not “The-Catholic-Family-of- the-Year” story. But it was just what I needed. Both then and now. And so, in the end, is everybody’s life, I think.

The sad thing is thinking that there’s something perfect against which we must model ourselves—and then fail to meet it.

No, life is not about becoming perfect. It is about becoming whole, becoming complete, becoming fully alive human beings. And that is never “perfect.” That is messy to the max.

Wednesday, January 1: Perfect is a warped shadow of what really is. Life consists of twists and turns, a maze of possibilities through which we wind our way to becoming everything we are.

Thursday, January 2: There is a difference between the perfect and the desirable. Perfect is a plastic imitation of the real, a counterfeit attempt to reproduce someone else’s definition of life

or standards. The desirable, on the other hand, is an attempt to make the imperfect just a little better.

Friday, January 3: “It is reasonable,” Samuel Johnson wrote, “to have perfection in our eye that we may always advance toward it, though we know it can never be reached.” Acceptance of what is, does not negate the hope of advancing.

Saturday, January 4: Perfect imitations of past pieces of new awareness are not art. “The artist who aims at perfection in everything,” Delacroix wrote, “achieves it in nothing.”

Sunday, January 5: Perfection, whatever there is of it in life, is not always as holy as it seems. Too often perfection comes more out of ego than it does out of commitment.

Monday, January 6: Perfection is the end of a process, not its beginning. That’s why they call it experience.

Tuesday, January 7: In our compulsion to be perfect, we have driven ourselves to the point where silver medals, the thousandths of a second between athletes on an Olympic podium, have become more a sign of failure than they are of success. How warped can we get?

Wednesday, January 8: “No good work whatever can be perfect,” John Ruskin wrote, “and the demand for perfection is always a sign of a misunderstanding of the ends of art.” When we realize what we lack, we are ready to join the rest of the human race.

Thursday, January 9: Perfection is not what being human is about. Perfection is simply not attainable in the human condition.

Friday, January 10: Perfection is not possible on earth, so why do we insist on measuring ourselves by its standards? We set ourselves up only to be disappointed in ourselves or jealous of others.

Saturday, January 11: When I am intent only on being perfect in life, I lose the joy that comes from learning to fail freely. Then, as Tennyson says, I run the risk of becoming “faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null, dead perfection; no more.”

Sunday, January 12: If God expected perfection, would we have been created in the first place?

Monday, January 13: Learning to accept the theology of failure is a far safer road to heaven than the theology of perfection will ever be.

Tuesday, January 14: The purpose of my imperfections is to enable me to live well, to act kindly, to be loving with others.

Wednesday, January 15: When we drive ourselves to be perfect, we drive ourselves to exhaustion, to temper, to disappointment and a sense of failure. We forget the simple joy of being alive.

Thursday, January 16: “Perfectionism,” said Hugh Prather, “is slow death.” Relax. Just give yourself a break.

Friday, January 17: Having a goal to aim at is a good thing; requiring of ourselves that we make it, on the other hand, is deadly.

Saturday, January 18: “Ideals are like the stars,” Carl Schurz said. “We never reach them, but like the mariners of the sea, we chart our course by them.”

Sunday, January 19: If we insist on everything in life being perfect, we doom ourselves to unhappiness. Better to find the joy of the nearly good enough than exhaust ourselves on the impossible.

Monday, January 20: “I dance to the tune that is played,” the Spanish say. It’s the grace to go on dancing, whatever the tune, that counts.

Tuesday, January 21: To say that a thing is perfect is to say that it cannot be improved upon. How boring.

Wednesday, January 22: “Growth,” John Henry Newman wrote, “is the only evidence of life we have.”

Thursday, January 23: Life is not meant to be perfect. It is meant to be perfectly capable of challenging us to be everything we are meant to be.

Friday, January 24: The truth is that no one has the perfect life—except those who are perfectly committed to make the best of the one they have.

Saturday, January 25: If my family had been perfect, I might have grown up thinking that I was normative, that everybody was supposed to look like us, that anybody who didn’t was inferior or bad or out of step. I might have grown up thinking that only Catholics went to heaven. But with a laughing Protestant grandfather and a loving Protestant stepfather, I learned young that that couldn’t be true, wasn’t true, would never be true.

Sunday, January 26: “I wanted a perfect ending…” Gilda Radner wrote, “Now I’ve learned, the hard way, that some poems don’t rhyme, and some stories don’t have a clear beginning, middle, and end.... Delicious ambiguity.” Yes, ambiguity itself can be delicious.

Monday, January 27: “Perfection” is the neurosis of those who believe that life was made for us to control rather than to grow into.

Tuesday, January 28: Humanity is a mixture of blunders. That’s what makes it so charming, so interesting to be around. Because none of us is complete, we all need one another.

Wednesday, January 29: Never be afraid to admit that you “don’t know” or “can’t find” or “couldn’t do” something. Our imperfections and inabilities are the only thing we have that gives us the right to the support of the rest of the human race.

Thursday, January 30: Beware the temptation to find yourself perfect. That is the day you will find yourself dead—either of body or of soul. “This is the very perfection of a person,” Augustine wrote,“to find out our own imperfections.”

Friday, January 31: The function of being human is to become the best human beings we can be, one insight, one mistake, at a time. Then, knowing the struggle that comes with trying and failing over and over again, we become tender with others who are also struggling in the process.

Discussion Questions

1. Is perfectionism something that you have struggled with? Are there certain parts of life–family, work, politics–where you feel that it is important to attain perfection? How has that affected you, and have you let go of it or become more entrenched in it over the course of your life?

2. Which daily quote in The Monastic Way is most meaningful to you? Why? Do you agree with it? Disagree? Did it inspire you? Challenge you? Raise questions for you?

3. After reading The Monastic Way, write one question that you would like to ask the author about this month’s topic.

4. Joan Chittister uses other literature to reinforce and expand her writing. Find another quote, poem, story, song, art piece, novel that echoes the theme of this month’s Monastic Way.

5. Sister Joan teaches that acknowledging our imperfections has the ability to strengthen our relationships with others, and to make us love them more. Has this been true in your experience?

Scripture

Christ said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” Therefore I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me.--2 Corinthians 12:9

Journal Prompts

1. Here are a few statements from this month’s Monastic Way. Choose one that is most helpful to you and journal with it.

• Having a goal to aim at is a good thing; requiring of ourselves that we make it, on the other hand, is deadly.

• If God expected perfection, would we have been created in the first place?

• Our imperfections and inabilities are the only thing we have that gives us the right to the support of the rest of the human race.

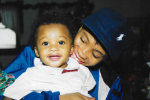

2. Spend a few minutes with this photograph and journal about its relationship to this month’s Monastic Way. You can do that with prose or a poem or a song or....

Prayer

The Serenity Prayer

God, grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change

the courage to change the things I can

and the wisdom to know the difference.

Artwork: by Karen Bukowski

Artwork: by Karen Bukowski